Buddha Way, Fourth Way

Every Day is a Good Day

Case 6: Yunmen’s Good Day

Yunmen taught, “I do not ask you about before the fifteenth of the month. Come, say something about after the fifteenth.”

And he himself responded, “Every day is a good day.”

As we all know, there’s a week-long sesshin in progress at the Temple, the culmination of 3 weeks of residency practice, the longest in-person practice period of the year. Some of us may wish we were at the Temple right now; I know I do. I’ve been sitting with this feeling for some time—since the beginning of the two weeks of residency practice—and it’s only intensified since the start of summer sesshin. Someone said to me the other day that there’s only one thing harder than going on sesshin—not going on sesshin. I wish I were there at the Temple, sitting with my sangha, having the sort of experience you can have on sesshin…

What sort of experience is that? Is it an experience that is unique to sesshin? Well, there is nothing like sesshin, and there are lots of good reasons to go on retreat. The three that occur to me right now have to do with the Three Refuges: I go on retreat to take refuge in Buddha, Dharma, and Sangha. But I take these refuges every day, and in times of difficulty (which will arise whether I am on retreat or at home), I remind myself to take refuge not in my usual distractions (my email, my tv shows, my reading, etc.), but in awakening, in the teaching, and in the support of my sangha mates.

Certainly it is worthwhile to go on sesshin. I may feel that sitting and doing nothing is not the best use of my time, I may have pressing matters to attend to—a new job, an ailing spouse, a contractor working in my house—or I may feel that I want to engage in some action that improves a world on fire, if only in a small way. But I am convinced by my experience on sesshin that no project for improving a tiny corner of the world has any prospect of avoiding evil and cultivating good and saving beings if I do not bring my practice to it, which means becoming aware of the role that is played by my own greed, anger, and ignorance…and sesshin is certainly an opportunity to see this.

Yun-men says, Every day is a good day. It’s always a good idea to go on sesshin. This is what I think when I sign up for sesshin, weeks, maybe months in advance: This is a good idea. The night before sesshin begins, I ask myself, Why did I sign up for this? After a certain period of sesshin, which can be a couple of days or a couple of hours, I find that I have entered the sesshin, and I’ve forgotten this question. And on the last day of sesshin, I say to myself, Every day—that I come home from sesshin—is a good day. I go home and indulge myself in all the goodies that the snack table has not provided—ice cream, potato chips, beer—and it may be a couple of days before I come to myself, before I remember my intention to take refuge in buddha, dharma, and sangha…

But if I’m lucky, sesshin has given me a clue about being at home. Yun-men says, ‘I do not ask you about the fifteenth of the month; come, say something about after the fifteenth.’ This is usually taken to mean ‘after realization.’ But I think that it’s a little trap that Yun-men has set for his monks—and for us. Do I believe that Zen practice consists of stages, or a series of ascending steps? Before Realization, Realization, After Realization. Before Sesshin, During Sesshin, After Sesshin. The koan says, Yun-men taught, Every day is a good day. Not that every day is a good day. On some days, you eat the bear; some days the bear eats you. On some days, sadness will arise, on others, joy—and everything in between. But whatever arises, it is the Dharma, it is my life, and as such, it is a good in itself, and this is a good day on which to meet it—actually, this is the only day on which to meet it—to appreciate it, to become one with it, to walk this way of practice.

Yun-men is teaching me about the habit of mind that creates stories: the story that if I practice long and hard enough, there will be a realization—and after that, things will be different; the story that my practice is not strong enough, but it will be strengthened by sesshin, and when I come back to my life, I will notice the difference. The story that life presents itself to me in distinct phases or stages that I can recognize and therefore manipulate in order to achieve a specific goal that I can remember and hold before myself.

So the distinction between On Sesshin and Not On Sesshin is not a real distinction, does not accord with reality. If I am unhappy because I am not on sesshin, if I miss my sangha mates and wish I were practicing with them in person—this is my sesshin! I am unhappy and at home, knowing that I have often been unhappy on sesshin, I have often sat through a long dark sesshin evening wishing I were somewhere else, wishing I were having a different experience. But on sesshin or no, what matters is remembering to meet that wishing, remembering that this wishing is my sesshin, is my life, that every day is a good day.

Whatever happens, this is my sesshin, this is my practice. Is that all right? I don’t think this attitude is to be had simply for the asking. What if I don’t accept my present circumstances? This is where the rubber meets the road. This is why we call it a practice. At least I can acknowledge that I must start from where I am rather than from some hypothetical or future place or sesshin opportunity that I was unable to take advantage of. I want to go on sesshin to take refuge in buddha, dharma, and sangha. But the Refuges are also Precepts, which means that they serve as a reminder of my intention to practice, no matter where I am, no matter what is arising in me. To practice, which means to investigate. Remembering this, I can truly say, with Yun-men, Every day is a good day—and mean it!

Thank you,

_()_

Stage Fright

The classroom is a very fruitful place for me to work, though tremendously difficult, since I suffer from a sort of stage fright in regard to teaching that makes it very hard for me to bring any inner work with me. A former student described me as “organized to a fault,” and because of my determination to stick to my agenda I never know what’s really going on in the classroom, whether my students are hanging on my every word or stupefied with boredom or floating somewhere in between. Stop and smell the roses, you may say. But that’s where the stage fright comes in. Underlying the highly organized agenda—is fear. I’m afraid to see that I’m not the teacher I imagine myself to be.

I’m laboring through a late-semester meeting of a creative writing class, carrying the proceedings with my insightful comments and helpful hints—and resenting it mightily. This is the moment to introduce an inner effort, I say to myself. But this means to acknowledge that things are not going well—or at least to acknowledge whatever is happening—and all of my external effort is dedicated to avoiding this knowledge. Working with an inner exercise in the classroom is like trying to submerge a buoyant object: the deeper I go the more resistance there is, the more likelihood of its bouncing back to the surface. But this time my misery spurs me on. There must be a way out.

Suddenly I find myself in a quiet place where there is nothing but myself and my students and the reality of what is happening between us, which is infinitely rich in nuance and possibility, but defines facile classification. It is a great relief to be in this place, and I wonder what I’ve been so afraid of. I become aware that I have two classroom personae, the one who hungers for the merest hint of affirmation and takes it as proof that he's a charismatic teacher, and the other who can interpret a student's scowl to mean that the entire class is a failure—and both of them are equally false.

Later I thought of this quiet place as the manifestation of the third force that enters when the tension between the impulse to work and the resistance of the external situation is sustained, and I remembered Gurdjieff’s description of "the one who is—but so weakly, so impermanently that he vanishes almost as soon as he appears." The new persona did vanish after a few moments, but I feel the wish to seek it again—as soon as the new semester begins.

Saint Pierce

My wife and I were having a familiar argument: she was singing her Needy song, I my Angry song. Suddenly I was aware that she had simply dropped it: she wasn’t singing any more. “Are you still angry?” she said to me. “No,” I muttered, through clenched teeth. She began to laugh; she could see very clearly what was going on with me. “Why don’t you just—stop pretending?” she said. So I did. I told her just what I thought of her Needy song and what I thought of her dropping it like that and what I thought of the cool, calm, and collected look on her face. And as I yelled, I began to hear the sound of my own voice, the voice of a bad actor, reaching for an emotion that wasn’t his, struggling to take himself seriously. Once I saw this, my Angry song fell to the ground. I burst out laughing. We both had a good laugh, and that was the end of the argument.

But the real punch line came a few seconds after I’d wiped the tears from my eyes and taken a deep breath. I suppose I was congratulating myself. I’d managed—with a little help from Susan—to experience my anger and not to take it so seriously. But in the next instant that anger was beside the point. I saw that I was really identified with the tight-lipped saint my wife had teased, the person who said he wasn’t angry. That was the person I believed myself to be, the person I had to be at all costs—cool, calm, and collected, in spite of all the indications to the contrary—and it was terrifying to see, if only for an instant, that it was a lie. I felt that my world, my conception of myself, had been turned upside down. I had gone forth to encounter the demon Anger and to wrestle it to the ground if I could. But the real enemy, the pretender, the liar—was St. Pierce.

I struggled for years to separate myself from negative emotions like anger by opposing them with an effort of attention. I hoped that something new would enter to resolve this opposition, a sense of freedom or detachment that I called separation. The alternative was that the emotion would eat me up alive, that I would be nothing but emotion, completely identified. But then I saw that instead of working with emotion, I was just trying to keep it down, that my attempt at separation was really a kind of repression—a refusal to acknowledge the presence of unwelcome feeling in myself. As long as repression masqueraded as work, there was no hope of seeing what was in me, no hope of real separation.

Once I realized this, I tried to encourage emotion to come forth from its hiding place, and my work was to feel it, to accept it, to be present to it with as much force as I could muster. This is the essential foundation for my work. But the true beginning came when I saw the persona that controlled the mechanism, the ‘I’ that tried to be above feeling—the plaster saint.

A paradox: You can’t separate from emotion if you’re determined to keep it at arms’ length.

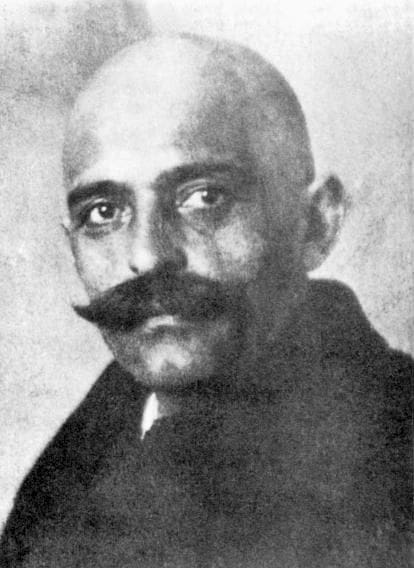

George Cornelius

When I visited George at his house on the Saturday morning before he died, he showed me a collection of talks by a group in Oslo that was dedicated, To George Cornelius: A Link between Heaven and Earth. And when I read this, I remembered that it was true, and that George had played that role for me. I remembered sitting in my garden with him on one of his visits from Oregon. He was talking about the wind, and he repeated something I’d often heard him say, the first line from the Gurdjieff grace, All life is one and everything that lives is holy. He went on to say that the wind, the air we breathe, is not merely a symbol, but an expression or actual manifestation of that truth. While I sat there with him, I experienced the truth of what he was saying, not just as an intellectual insight, but in my body and my emotions. For me, it was a kind of magic, something utterly unlike my everyday experience, something I had never expected to know. I thought I had forgotten that moment, but I see that there’s a part of me that cannot forget it. And George provided such a moment for me not once, but many times. I’m a person whose faith in the existence of higher worlds and in the pilgrim’s progress is a little shaky. George strengthened that faith, not so much by what he said or did, but by the example of his being. This was George’s gift, not just to me, but to many people. It is not a small thing.

George was a teacher for me, and one of the most valuable lessons I learned from him was how to say No. George was a person who knew what he wanted and he made no bones about asking for it. At first I was a little overawed by this aspect of his personality and then I began to see how it could help me. George and I had our struggles—he wanted me to have my own group, he wanted me to write a book, he wanted me to index Beelzebub—but I found that if I made contact with my own experience and my own voice, if I discovered what I wanted and what was right for me in the present moment, I always had George’s respect, even if it wasn’t what he wanted, or said he wanted. George was a sounding board for me: he never failed to make me aware when I was not being entirely honest with myself, but when I had my moments of truth and authenticity, he backed off and left me alone with them. That was what he really wanted, that you should come into possession of your own experience, whatever it might be, in the present moment.

After I learned—or thought I learned—to say No to George, my relationship with him changed. He became more like a member of my own family, and I like to think that he felt the same way. Indeed he gave me something I frequently sought in vain to find in my own family: an interest in my life and in the things that concern me most deeply, and an appreciation of what little I was able to do for him in return. Last December I went to his house and strung some Christmas lights for him on the tree and the well in the front garden. It was a comic scene, myself balancing on the top of the step-ladder while I lassoed the tree with the string of lights, crawling along the ridge of the well with the power cord between my teeth, while George sat muffled up in coat and blankets in a chair on the lawn, demanding to know where my attention was and urging me to put sensation into my frozen fingers. Since it was still daytime, we couldn’t really see what the lights would look like. But when I got home that evening, there was a message from George describing the effect of the lights as he drove up to the house in the dark and thanking me for giving him that pleasure. It was a small thing, but he didn’t fail to acknowledge it.

As I sat at the kitchen table with George for what was to be the last time, I found that we were engaged in a familiar struggle: he was asking me to do something—and I was refusing. I was squirming a little too, instead of just being there. I guess it just goes to show that no matter how well you think you’ve learned a lesson, there will always be more opportunities to put it into practice. George had one last piece of information to impart to me; he informed me with great seriousness that Gurdjieff’s successor—would be an Irishman! Since there was no one else in the room at that moment, you’ll just have to take my word for it.

George once asked me to write a poem about Gurdjieff. It has to do with Gurdjieff, of course, and his relationship with his father as it is described in Meetings with Remarkable Men. But since it also has to do with George and me, I’d like to append it, by way of saying thanks to George, and God speed.

Where is God now?

My father said:

God is in Sari Kamish

Fastening happiness to the tops of trees

Making double ladders

So that people and nations can ascend and descend.

In the evenings

He sat outside and looked at the stars.

Nothing disturbed his inner peace

So long as there was bread

And quiet for meditation.

I wished with all my heart

To be such as I knew him to be

In his old age.

Where is God now?

On Rue des Colonels Renard

I sit in the attitude he taught me

An old man

In my ears the sounds of children's voices

Monsieur Bon Bon

Feeling the sun warm

The ruin of my body

I breathe God

In and out.