Seeking with Empty Hands

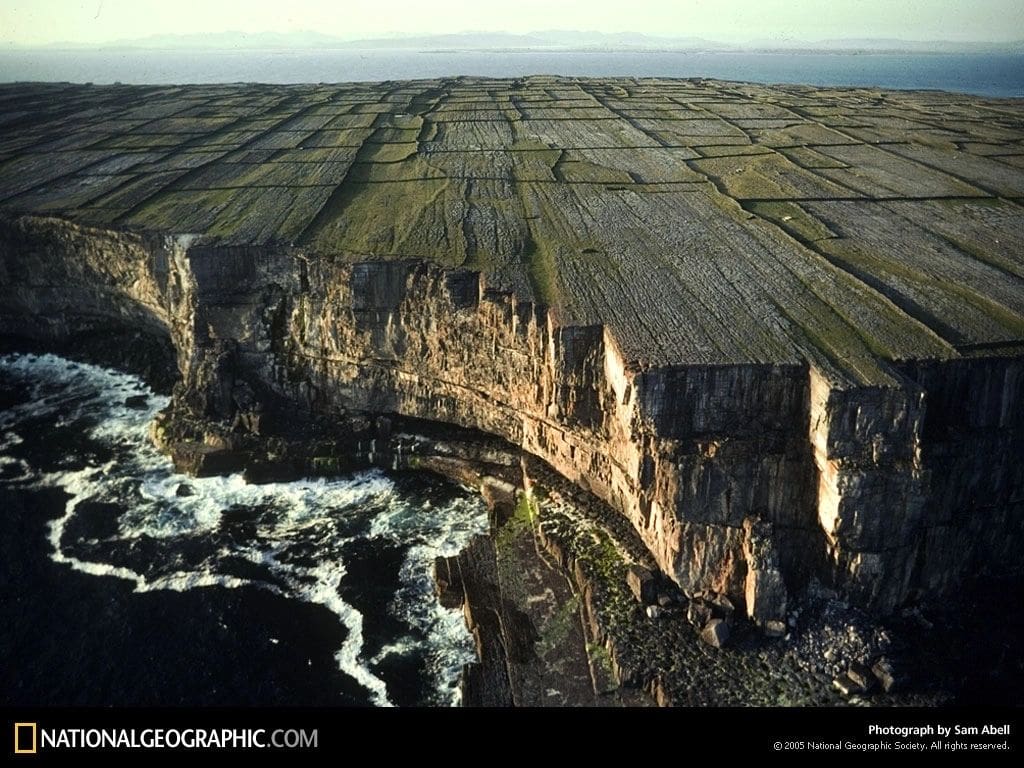

I just spent a week visiting family and friends in Ireland, along with my daughter and my daughter-in-law. I was born and grew up in Ireland, but apart a couple of brief journeys for the funerals of my parents, I haven’t spent any time there in more than 30 years. This trip was instigated by my daughter Becca, who had never been to Ireland, and I had a lot of anxiety about it. How would Becca and I get along at close quarters for an entire week? What would she think of my Irish friends, who are graybeards, most of them, like myself? But also, How would I feel about being in Ireland? I have a very strong attachment to Valentia, an island off the west coast where I spent summers as a child but of course as an adult I chose the way of the emigrant, like so many before me.

Well, in the event, it was the trip of a lifetime, and I came back feeling nourished by my relationship with my daughter, by friends from many periods of my life whose hospitality knew no bounds, and by the renewal of my connection with a couple of family elders for what may well be the last time.

And yet while I was there, in the midst of a great deal of eating and drinking and walking in the out-of-doors, I felt the lack of something: my sangha, of course, my wife Susan, who had to stay at home, and a certain kind of practice to which I have become habituated. Ireland is a slower country than the US of A, but oddly enough my experience of traveling with Becca and Liz and visiting friends and family at opposite ends of the country reminded me of a phrase from the Eagles song “Life in the Fast Lane”: Everything all the time. When I am at home, I have a practice schedule from which I rarely deviate. I like to joke that it would be easier for me to skip my breakfast than to miss morning zazen. I settle in, thoughts settle down, and I devote myself to not knowing, to being a person who has nothing to do. Rushing about from pillar to post, from town to country to island and back to town, I barely had time to draw a conscious breath. And I was continually saying to myself, this is very special, this is peculiarly wonderful, and yet if I could only bring more awareness to it, it would be more wonderful still.

This makes me wonder if the formal practice I am accustomed to at home is a subtle attempt to calm myself, to bear all smooth and even, to create a special state of immunity from the natural ups and downs of life. That would be a sort of denial of the complexity and the richness of my life, here and in Ireland. It is literally incomprehensible to me that I should have these apparently disparate places in my life: the remote island where I grew up, for which I still have a longing, and the comfortable home and garden I share with my wife in Waltham. My intuition tells me that these places are not different, that it is the same life, here and in Ireland and so does the teaching, presenting this truth for me to confirm in my practice and, fundamentally, in my experience: all things are one family, with or without realization.

Another Irish immigrant, Frank McCourt (of Angela’s Ashes fame) wrote a book called The Irish and How They Got That Way. To analyze how I got here can be interesting or merely confusing, but it’s beside the point, at least as far as practice is concerned, or rather it’s the dharma arising as interest or as confusion. What matters is to engage, to be wherever I am, to meet whatever arises, to live it to the hilt. A friend asked me, Did you ever imagine you would be here after all this time with your daughter? What is it like? Well, this brought tears of gratitude to my eyes; if Becca hadn’t wanted to “explore my roots,” as she put it, I wouldn’t have been there at all. But what is it like? What a question! The trouble with words is that they oblige you to try to say what something is by saying what it is like, which can never be what it is. So my answer was, I do not know what it is like. I only know that it is peculiarly wonderful, that my feelings range from joy to sadness and back again in a disorderly fashion, and that each feeling that arises can only be fully experienced for what it is.

Was there something I was seeking? Is there something I’m bringing back? Perhaps it is best not to seek, not to reach conclusions, not to make a distinction between “everything all the time” and coming home and sitting at ease. Best to go forth with empty hands.

Seeking it yourself with empty hands

You return with empty hands

In the place where fundamentally nothing is attained

You really attain it