Pacifying the Mind

I attended the online sesshin last weekend. We referred to it beforehand as the “short” sesshin since it ended on Sunday rather than Monday, but I concluded afterwards (and I think many other participants did as well) that its not appropriate to apply the terms “long” or “short” to a retreat. A sesshin is complete in itself, as is every experience, and if I am preoccupied with the duration of the sesshin, I am going to find it difficult just to get through it, whether it is long or short if I do not miss it entirely, in my grasping at what has just happened or my anticipation of what is to come. In this way, a sesshin embodies our practice by pointing to just-this, the full experience of whatever happens to arise, not only as the way to get through it, but also as the way to come into full possession of it, and of my life.

I learned this lesson not once, but twice over the duration of this “short” retreat. And I’ll probably learn it again on my next “long” retreat. The sesshin began on Friday evening, of course, but I love early morning sitting, and so I was looking forward to the early Saturday morning practice period as the real beginning of the sesshin. And so it was: just sitting, all things at rest, no need to understand or struggle to get free. When suddenly, in the midst of this sitting, the idea for a new writing project began to arise. And not just the idea, but the story itself, the dialogue, the description, the narrative voice, unfolding of itself without any help from me.

A little background here: I’m a fiction writer, I’ve published a couple of books, and I’ve had a writing career which has been quite satisfying and now seems to be drawing to a close. My agent died prematurely, I’ve written a couple of novels which a new agent could not find a home for, and I have no inclination to write another that nobody except my wife will read. But that entails the loss of the pleasure and satisfaction to be found in writing something and writing it well. I’m at a loss to know how to proceed with the activity of writing that I’ve done all my adult life (apart from writing out my dharma talks before I give them). And now suddenly, in the midst of sesshin, I see exactly what I might write and how to write it. I am actually doing it, writing it while I am sitting, or rather it is writing itself, and I am watching it happen.

I’ve only had this experience once or twice in my writing life, and there’s something exhilarating about it, it feels like a contact with the vast unnamable source, like a gift from the universe. There’s only one problem: I’m supposed to be sitting zazen, I’m on sesshin. Am I really observing the spirit of the sesshin guidelines? Silence, stillness, custody of the eyes (and the mind?). What about do your best?!

Later in the day, I find that I haven’t gotten enough sleep, and I’m struggling to stay awake during the teisho. I need to shake off the sleepiness and attend to what is being said. And I reproach myself for not taking care of business, for not retiring early on Friday night and making sure I was well rested.

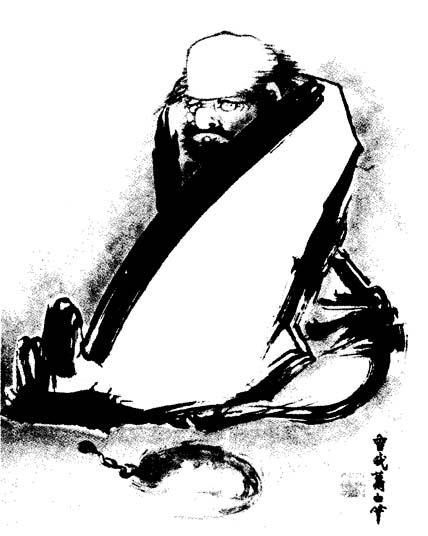

The teisho is about the famous encounter between Bodhidharma and the 2nd patriarch Hui-ke, in which Hui-ke cuts off his arm in order to get Bodhidharma’s attention, a detail that’s always puzzled and annoyed me. Is that what Zen requires? Hui-ke is standing knee-deep in snow, trying to get Bodhidharma’s attention, and I’m up to my neck in sleepiness, trying to bring my attention to bear. What is it that’s required?

And then a phrase from David’s talk penetrates my sleepy mind. He says, referring to Hui-ke’s sacrifice (I think): and it is everything. Of course, I say. What is required? Oh, just everything. And what is this everything? Well, it is not only my sleepiness and my self-reproach, but also it is my casting about for something that will alleviate my distress, it is my confusion about what is required. It is the wall I am facing and the self that faces it. Nothing is required except to face it. Nothing is required except everything!

Hui-ke says to Bodhidharma: “The mind of your servant knows no rest. Please pacify it for me, Master.”

B: Bring me your mind and I will pacify it for you.

H: I have searched and searched and I cannot find it.

B: I have completely pacified your mind.

And Hui-ke has realization. What does he realize? He realizes the mistake of taking the mind as separate from everything else, as a separate entity capable of detached observation. Searching for this kind of mind, he cannot find it. Where is the line between the mind and everything else? How can the eye see the eye? The mind is everything, and everything is the mind.

Whether it’s a spontaneously arising fictional story or the fumes of sleepiness that confuse my brain, this is IT. No need to chase either one away. But how to be convinced of this? How to realize that whatever arises is the Dharma, the living proof of no-separation, of no-self and other?

This is IT. We use this phrase all the time to point to a truth of the teaching, but it’s easy to pay lip service to it and to remain fundamentally unconvinced, to continue to harbor the belief that upright sitting with all things at rest is certainly IT, but surely my runaway thoughts are not it, nor my dislike of washing the dishes, nor my self-reproach. But buddhas and the patriarchs are not kidding: this is IT!

This is the koan of this moment, of my life as a student of the Zen way. This is not a practice you can do, and yet there is the urgency of impermanence, the cliff-edge of life and death. Realization will always be an accident, and yet we can make ourselves accident-prone, not by striving for a special state of immunity from distress, but by the practice of cease-and-desist: the practice of just-rest-and-cease: be cooled.

The Dharma is an intimate, almost homely experience, like coming home and sitting at ease, always right here, closer than the door, than the vein in your neck. Knowing this, whenever I know it, whether I am delighting in the arising of an idea for a story and up to my neck in self-reproach, I have a chance to embody the unsurpassable Buddha Way in everything that arises.